Moms in I Promessi Sposi

In honor of Mother’s Day and of all moms, real, adopted, and imagined, I would like to think about the mother figures and the role of the mother in I Promessi Sposi. Plus, I am a little stuck on Agnes. I admit it. What is she doing as a major character in this novel? I would also like to think about how digital humanities tools might help me think about the moms in this novel. First, it strikes me as unusual for a mom, let alone several moms, to have such an active and positive role in a literary narrative. I am more used to either bad moms/step moms (Grendel, Gertrude from Hamlet, Cinderella’s step-mom) or dead/lost ones (every fairy tale). [Note the gratuitous Shakespeare reference].Moms are a burden for the young hero who needs to grow up and find his/her way in the world. Moms (in literature) remind us that our hero used to be someone’s baby and might need to be reminded to wear a sweater on a chilly evening. This is not really promising hero material.

But in Manzoni’s novel, we just keep acquiring moms. Agnes is mom to both Lucy and Renzo throughout the text; they rely on her for advice, companionship, safety, and honesty. She travels with them, and then even travels on her own. Lucy acquires more mothers: The nun of Monza (not a great mom, but she does serve as a surrogate), Donna Prassede (also not a great mom but she does help keep Lucy safe), and in the lazaretto, the merchant’s widow, whom Lucy titles a second mother and who is welcomed into the family with open arms by Agnes. Meanwhile Agnes has shifted from being a respected mother-in-law for Renzo to an actual mom (or at least that’s how I read the apparent growth of affection). They decide the future together. And of course we have other mom figures—the tragic mother who lays her dead daughter on the cart before comforting the next child marked for death, and the tailor’s wife, mother of cheerful and lively children.

The events of this novel tear our little would-be family apart and disperse them throughout Italy, but as national events catch our characters up in a larger historical narrative, the definition of family expands as a result. A tiny village can sustain a tiny family; the national landscape requires more people for survival, it seems. And those people are largely (not exclusively) moms. Why? I have a few guesses—most of which involve me doing more research and figuring out if moms are a standard feature of novels that overlay or simply articulate a decidedly Catholic narrative to the cultural landscape. Lucy seems to need female companionship—a chaperone for her virginity. But there’s also the Virgin Mary as intercessor. Do moms in this novel—or other novels—provide living stand-ins to enact the ultimate Mom’s protection? I confess my own area of study leaves me inadequately prepared to answer these questions. I hadn’t considered before now how, well, Protestant British and American lit really is.

So how might I use digital humanities tools to help me answer my questions and overcome my literary handicap? I thought about word clouds. Perhaps, with much manipulation, I could target mom words (names, variants of mother) and look at their frequency in each chapter. But ultimately, I don’t think this would net me much unless I also compared it to, say, dad words. What might be more useful is a kind of Mom Map—one that perhaps tracks the physical movements of Agnes, Lucy, and Renzo and then overlays the other moms onto the map where they come into the story. This might shed light on the purpose of each mom figure and the impetus for growth in each main character. I also think creating a bubble chart might both help me ask useful questions and illustrate the influence of moms in this novel. Mom Bubbles! Relative influences, connections, and overlaps might readily be discerned through these visual metaphors. I do think this is the kind of question that can benefit from a digital humanities approach in conjunction with traditional scholarly inquiry. What do you think?

Recently, our class visited the Spencer Museum of Art on the University of Kansas campus to view artwork that would help the class visualize the characters and setting of I promessi sposi. Although Manzoni describes each character's dress and appearance in depth and guides the reader to envision the abhorrence of the famine and plague of Milan, it is useful to examine artwork from the time period in which Manzoni was writing and the time period in which I promessi sposi takes place in order to see another artist's point of view. There are four pieces in particular that I would like to discuss: head of a monk (artist unknown), Two gentlemen of Verona, Act V Scene III by Angelica Kauffmann, an untitled work by Giuseppe Bernardino Bison, and The Plague of Phrygia by Raphael.

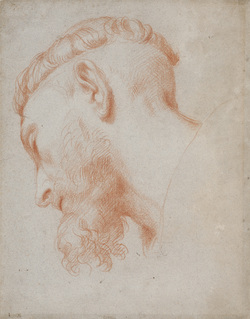

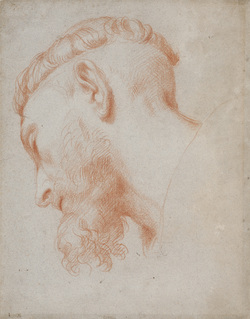

The first piece of art, head of a monk, is a chalk sketch done by an unknown artist from a Roman school. The sketch was done during the time period in which I promessi sposi takes place. This work is an excellent visualization of the character Father Cristoforo. In I promessi sposi, Father Cristoforo is friar of the Capuchin Order, and this sketch helps the reader to vision the hairstyle and beard of a friar. Friars practiced tonsure, the removal of their hair, to show that they were slaves to God. In this sketch, the monk is deep in thought, shying away from the viewer. This piece of art helps the reader to imagine the stress Father Cristoforo's face when he is trying to decide how to help Lucia and Renzo, or perhaps how to confront Don Rodrigo.

The second piece of art, Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act V Scene III, is an engraving done by Lewis Schiavonetti. The original artist Angelica Kauffmann completed the work sometime between the late 1700s and early 1800s. The piece depicts a scene from Shakespeare's 17th-century comedy Two Gentlemen of Verona. The scene is being reinterpreted during the time of the Schiavonetti. This piece was completed during the time that Manzoni was writing I promessi sposi, another example of an artist reinterpreting the work of previous artists. This piece also helps the reader to speculate the dress and demeanor of the characters of I promessi sposi. It also provides an example of female-male interaction. In contrast to this work, the character of I promessi sposi show little affection, even the betrothed Lucia and Renzo.

The third piece of art is an untitled work by Giuseppe Bernardino Bison. This piece was completed sometime during the late 1700s and mid 1800s. The sketch was done with pencil, pen, ink, and wash and depicts a women with a grapevine, a man with a laurel wreath, and another woman on horses. Since this piece was also done during the time that Manzoni was writing I promessi sposi, it is inevitable that the viewer can utilize this piece to imagine the dress and demeanor of the characters. In my opinion, this image can be used to envision the scene in which Lucia and Agnese flee from Lecco. The women wear hooded tunics to hide their faces and Lucia holds a grapevine. In the Old Testament, the grapevine is a sign of the chosen people. Lucia represents the truth and the light in I promessi sposi. Her presence helps the Unnamed to abandon his life of sin for one of morality. Lucia's virtuous nature and devotion to God are matched to the woman in this piece.

The last piece of art, The Plague of Phrygia, is an engraving done by Marcantonio Raimondi sometime between the late 1400s and early 1500s. The original artist Raphael recreated the plague that devastated the ancient kingdom of Phrygia. This piece can be utilized for the reader of I promessi sposi to visualize the plague that struck Milan in 1629. In this piece, there is a clear division between private and public, or rich and poor. However, in I promessi sposi, Manzoni describes how the plague made class division null. The plague of Milan forced everyone to dress the same, eat the same, and die the same. In this piece, there is also a statue in the middle, which divides the public from the private. The statue represents either political or religious institutions that stands above everyone else and remains untouched by the plague. This is similar to the plague of Milan in which the highest political and religious figures remained unaffected by the tragedy.

As I look at my calendar, I realize that we are quickly approaching the end of the semester (which seems unbelievable for many reasons, including the fact that it feels like we still have quite a bit to read in order to resolve many of the characters' problems!). Throughout the semester, I've kept expecting for all of it, the digital humanities and Manzoni's novel, to all come together in an "aha!" moment, a moment of clarity where it all clicks. ....I seem to still be waiting.

So I ask myself (and my classmates), how does it all come together? Will we reach this "aha" moment in the upcoming weeks, where Manzoni's novel and the digital humanities come together in a way that can be represented which is not only visually appealing but also informative? (I certainly hope so, since that will be the goal of our final portfolio!) Or is the concept of welding together the digital humanities with 19th century literature something that one has to continually push towards? It feels as though we are only beginning to get a grasp on how to commence expressing our ideas and Manzoni's novel accurately through the use of digital tools. And yet, we have been working on this project for close to four months now.

I ask these questions almost rhetorically, in hopes that the next few weeks provide at least some answers. Yet I can't help but feel that a semester does not seem to be quite enough time to cover such a growing and relatively new way to think about literature.

We’ve come to the point in the semester where we are finally getting down to the nitty gritty of a language: the words themselves. Not just how many words are counted in a specific excerpt, which has been demonstrated by our Word Clouds, but word choice itself and what it really means. This is where we run into some issues. Mainly, the occasional but glaring differences between the original Italian version of I Promessi Sposi and its English translation.

As a class, we have begun to compare translations with our assigned portfolio chapters and have found some interesting discrepancies. Some are small, such as the use of one particular word in my chapter, “sentenza,” as compared with essentially every synonym you could possibly ask for in the translated text (sentence, verdict, decision, observation, etc.). However, some are more important. For instance, we discovered that in certain chapters, the character Lucia’s (Lucy) name has been used more in the Italian version than the English one. Additionally, the Archbishop Federico Borromeo was not mentioned by first name at all in the English version, but several times in the Italian text. This may seem like the inconsequential tossing around of synonyms and proper nouns, but are the readers getting the same message or feeling from both texts? Are we subject to the influence of the translator’s discretion more than we have ever believed?

It is often said in foreign language classes that there are some words, phrases, and meanings that just cannot be translated exactly. To this, I wholeheartedly agree, and maybe this is the problem. However, it is impossible and ridiculous to always expect texts to be read in their original languages. I personally have never even thought about the possible differences between one book and the other, although they are intended to be the same thing. We have more investigating to do, but it seems as though the words and sentiments that sometimes slip through the cracks of translation not only lose the significance of the original text, but can also create something entirely new.

At this point in the semester, I am beginning to feel the woes of technology. This is the first semester in which I have had to learn this many new technological platforms and it has brought an entirely new set of problems. I feel like our group is very lucky to have Professoressa Hall and Keah Cunningham to guide us through. If we were on our own, we probably would have all given up by now, or at least, I would have. Please do not misunderstand me, I am loving all of these new platforms and I think the use of them will result in a fantastic final portfolio at the end of the semester, but at the moment I am frustrated.

VoiceThread, probably one of the coolest technologies we have learned about, is causing me the most trouble right now. Over the past few weeks, I have tried to do voice recordings to accompany my section of the classes “Nun of Monza” VoiceTread. I am sure the issues are largely stemming from my need to record and constantly rerecord (about 20 times), however, I can’t help but be discouraged a little at my inability to get anything to post. Foolishly thinking I could make it work on my own; I have postponed emailing Keah about this issue until today. She promptly emailed me back with a list of possible hindrances and I plan to try out her solutions here in a few minutes. I’m sure this will all be resolved momentarily but it does all make me think, What about the people who don’t have a Keah?

For those who do not have a tech savvy friend like Keah, VoiceThread appears to have a pretty comprehensive help page that could be helpful.

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading.

Jordan

As we return to class after a long spring break, the class faces many middles: the book, the term, the portfolio. As we ask whether or not the characters have developed, if themes have become more complex, and if we can predict an outcome for many of the novel's plot lines, I wonder if we can ask the same about our own skills as digital humanists.

I think that the other blog entries from the first half of the semester would suggest a positive answer. We have moved from wariness about digital tools to a critical selection and application, albeit with much more ground to cover. We have posed very broad questions and have suggested tentative answers that will be tested with more analysis.

My challenge to the class (and to myself) will be to explore how all of these activities and readings make us think differently. Manzoni, with his overt and subtle agendas, was attempting to reach his reader and create a different way of thinking, as well as entertaining. Can DH do the same for our understanding of the building blocks of literature?

Saint Agnes of Rome is the patron saint of engaged couples. I find it hard to overlook this convenient bit of allegory in a novel titled I Promessi Sposi. And yet, our own Agnes is an unlikely saint, well-meaning but not particularly wise. Like the other characters in our text, she must find her way in an unjust world. This small but significant nod to the verse and prose romances popular in the 16th century, rife with allegorical characters wandering through a treacherous landscape has haunted my reading of I Promessi Sposi for weeks in the form of Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590; 1596). Not that Manzoni had read Spenser; no, that would be too much to hope for. But we know Manzoni did read English authors (Swift, Pope, Johnson) and traveled to London. Spenser influenced generations of writers, including Milton ( Paradise Lost), and so if we can say nothing else, we can argue that whatever Manzoni read in English, Spenser lurked in the margins. We can say they share similar sources in Ariosto and Tasso. Novices to Spenser’s epic struggle to keep the allegorical and the personal balanced. We are too familiar with novels, these days, to keep the allegorical readily at hand. If we read the text as largely personal, we regularly ask ourselves why Redcross is so darn stupid. Seriously. He makes terrible decisions! If we read it as purely allegorical—well, frankly, it’s just too long for an allegorical tale of holiness. Get to the point already, Spenser. We must read The Faerie Queene with a double consciousness—an awareness that the narrative exists on at least two planes, and those planes are always in play. His bad decisions are allegorical representations of our own failures as fallen humans—a spiritual journey towards holiness taking place on the psychic landscape of the soul, which looks amazingly like pastoral England. There be dragons, but mostly in our own minds. His adventures seem ridiculous (who trusts a ruler named Lucifera?) but they take place as much inside his mind and soul as outside in a physical world. The text, essentially, works from the outside in, giving us the borrowed armor of holiness (see below), and filling the armor with a worthy man through the lessons of the personal and national religious experience. In short, he’s a character type much like our Renzo at the beginning of I Promessi Sposi. Renzo, as we leave him in chapter 17, is still wearing his wedding clothes—his own armor of “husband”—but has yet to fill those clothes with a man worthy of the title (or worthy of the girl, who is clearly related to Una in some complex literary geneology). Manzoni’s genre (the nascent Italian novel) prioritizes the personal over the allegorical, but still, still, there is Agnes—our patron saint of engaged couples. When Renzo becomes entangled with the significant historical moments of the text, I wonder at the allegorical meaning for the national narrative Manzoni presents his readers, but also for the character himself, engaged (ahem) in becoming more than engaged. He is a rustic clown, a “simpleton,” who is slowly filling in his suit of borrowed matrimony with the mind and soul of a worthy husband. As previous bloggers have noted, we see this most graphically when the historical and the personal meet in the text. But we also see it when the generic (chivalric romance) meets the interior of the character (novel). In Chapter 17, our exhausted and despairing hero weaves his way forward, keeping the ‘straight and narrow high road’ in his sights but avoiding the dangers it threatens. He has, essentially, lost his way—a fugitive from (mistaken) justice, he cannot take the high road physically or spiritually. Finally, he stumbles through a dark and fearsome wood, seeking shelter and sanctuary (the land beyond the river). Paths and woods punctuate chivalric romances. Paths, especially the ‘easy path’ beckons the unwary traveler to fall ever deeper into error. What are we to make of the paths our hero travels in this chapter? Are the high roads of Lombardy paved with the slaughter of innocents? Is our hero so lost that he sees danger where danger does not dwell, eschewing the straight and narrow for endless wandering (our knight errant—error as synonymous for wandering)? Woods harbor monsters. The dense canopy blocks the light (The Light—of reason, of God, of clarity) and casts the hero’s mind into murky darkness. Redcross suffers these tropes many times over; our Renzo too meets his literary ancestors on the road and in the woods. He nearly gives up before hearing the sound of running water. And, at the border of despair and deliverance, he prays. He finds a new high road, and in the dawn light, an alternate path to spousal bliss. No doubt more wrong turns await his future. I would very much like to bring in language here and discuss the words, the style, the national and personal identity shaped by language in this passage, but that is way, way beyond my abilities. With any luck, my ramblings of English poets and chivalric heroes who hail from humble stock make sense for the Italian too. Quick introduction to Spenser and The Faerie Queene for the uninitiated Edmund Spenser (1552-1559) was interested in establishing a decisively English verse style for his national epic. Like Manzoni, he wanted to “renew language to its foundation,” and for Spenser, that meant harkening back to Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343-1400), known in the sixteenth century as the father of the English language. He produced the first national epic poem of England, The Faerie Queene, which contains six books organized around virtues (holiness; temperance; chastity; friendship; justice; courtesy). I am only obsessing about Book 1: Holiness, although all the virtues do come into play in Manzoni’s novel. Spenser was also greatly influenced by Italian writers (of course!), particularly Tasso and Ariosto, and as such, his epic is a grand verse narrative of knights errant (male and female, fyi) and royal personages wandering around the allegorical British landscape. SO not I Promessi Sposi, right? But bear with me. Book one has two heroes—Redcross and Una. Redcross, we learn much later in the story, is really Saint George, patron saint of England and Dragon-Slayer extraordinaire. Una is the daughter of Adam and Eve—she wins the Holy contest, hands down. She does get in a pickle or three, mostly because Redcross ditches her in a (corrupt) religious house while he heads off for new adventures, but she is wise, sensible, and, well, holy. She makes good decisions, unlike her future husband. Redcross, on the other hand, is a poser. When we first meet our hero, he is wearing borrowed armor and fighting with his horse (not a good sign). Externally, he’s a knight on a quest; internally, he’s a clueless country boy who begged the Faerie Queene (allegorical reference for Elizabeth I) for a quest and got this gig. He has no idea what he’s gotten himself into, and he has to learn on the job. The entire text is allegorical—he travels with a dwarf (human reason) and fights the monster Error who lives in the Wandering Woods before bumping into the evil characters of Duessa (two faced) and Sans Foy (no faith). I could go on—you get the idea. But it departs from its overt allegorical frame by also creating characters with psychological depth—they grow as characters, they have a modicum of interiority unusual for this genre. We read them as real people.

Say hello to the next big thing: VoiceThread... or is it? Recently our class has decided to investigate the appeal of this new, interactive collaboration and sharing tool that enables users to add images, documents, and videos, and then other users can add voice, text, audio file, or video comments. According to the VoiceThread website, the collaboration tool is defined as:

"With VoiceThread, group conversations are collected from anywhere in the world at any time and shared in one place, all with no software to install. A VoiceThread is a collaborative, interactive, multimedia slide show that holds images, documents, and videos. It allows people to navigate through the slides and leave comments in 5 ways: using voice (with a microphone or telephone), text, audio file (for VoiceThread Pro users), or video (via a webcam). Share a VoiceThread with friends, students, and colleagues so they can record comments, too. Users can doodle while commenting (drawing annotation overlays), use multiple Identities, and pick which comments are shown through Comment Moderation. VoiceThreads can even be embedded to play and receive comments on other websites, and they can be exported and saved as a file on your computer, a CD or flash drive so that you can send them in an email or play them as an archival movie on a digital device."

Copyright © 2013 VoiceThread LLC So, how will a class focused on Manzoni in the Digital Age utilize this tool? First, students and teachers can upload screen shots of specific passages from I promessi sposi and contribute annotations. Contributors can make note of reoccurring themes, symbols, diction, parallelism with history, etc. Second, an image can be uploaded to be analyzed for comparison to the novel. For example, an image of Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini, or Our Lady of the Conception of the Capuchins, a capuchin crypt in Rome, Italy may be a useful to analyze in comparison with the character of Fra Cristoforo in I promessi sposi. Third, a video clip of scenes from the movie I promessi sposi could be uploaded and analyzed in comparison to the novel. Fourth, other documents can be uploaded and comments and critiques shared amongst the users. For example, the class is currently working on a timeline that parallels the events of I promessi sposi with the life of Alessandro Manzoni; VoiceThread could be utilized to gain input from all users and have a real-time discussion outside of the classroom.

I Promessi Sposi combines the critical allegorical components to

help us comprehend the struggles that faced a young, and struggling nation that

so desperately yearned for independence. Touched upon in earlier blogs, we see

Manzoni’s interpretation of a hot-headed Renzo who is swept up in passion but

lacks the maturity needed to accomplish his ultimate goal of marriage or in a

historical context, unification. Similar to these hidden elements of foreign

blockades and Don Rodrigo’s wickedness, we must place ourselves in this context

to sympathize with the Risorgimento. We have also been introduced to a brand new

format where we attempt to bridge the gap between literature from two centuries

ago, with a digital connection of our own that looks to transcribe and unearth

Manzoni’s political and social relevancy.

With the assistance of Word Clouds and Timelines, we will be

relating this concept and struggle for identity within our current society. Word

Clouds provide us with the option to take a more examined and thorough approach

to the crucial themes and essential literary elements to I Promessi Sposi. With

this helpful tool we often uncover a hidden agenda of the author that may have

otherwise gone unnoticed.

The timeline is beneficial in piecing together the main events

from the plot of I Promessi Sposi and comparing them to the Risorgimento in an

organized fashion. We are now able to have a clear frame of reference when

discussing both the literary movement and Italy’s push for unification and

ultimate independence. In congruence with our digital adaptation of this novel,

it is possible and efficient to extract the key ideas and specific words to

place greater importance on this time period. By having a detailed account of

how often certain words appear in Manzoni’s work we can achieve an in-depth

analysis of each character and how they relate to one another.

This representation will take a little bit of getting used to

and perhaps some growing pains but we anticipate a positive outcome in bringing

Manzoni to a modern audience. If we are able to uncover the hidden agenda of

Manzoni and do so in a digitally advanced manner we have already succeeded.

In addition to how easily Manzoni’s political motives can be discerned after the initial “Lightbulb Moment” of the reader, one can also see that social disorder is an important and all-too-familiar matter when it comes to the changes that Italy was undergoing during the times in which the novel was set, written, and even across the world today.

Throughout history and especially in I Promessi Sposi, political and moral allegiances changed with the tide, many people (especially the noblemen around Don Rodrigo’s table) running to support the newest and greatest leader – the one with the most money, the biggest army, the best manipulating power, and the most social connections. Is this really what comprises humanity – completely forgetting moral obligations, disrespecting people as esteemed as Padre Cristoforo, blaming others for times of hardship (famine, disease, etc.) and acting as though the “right” to stomp all over those of lower classes actually makes them lower people? The question here is, "Why?" Why is it that this vicious cycle never seems to end? We have seen this happening in our lifetimes as well as in literature and history books, yet attempts at different forms of equality (or at least stability) immediately blow away with any breeze of uncertainty for one’s own “top dog” status. Are Manzoni’s depictions, several Revolutions, and our own measures all for naught?

I Promessi Sposi was first published almost 200 years ago, and the uncanny prevalence of his main topics led me to pose a second question: with this recent realization (at least on my part), how can we accurately represent the passion, the sadness, and the struggles – the human element – of his novel with digital formats? These issues have been around for so long; is it enough to create timelines with pop-up blurbs explaining the story of Lucia and Renzo, or to assemble pictures, videos, and intricately manipulated word clouds depicting our impression of Manzoni’s words on today’s audience?

The societal woes that Manzoni illustrates are not new, and most likely will continue long past you or I have moved on to, let’s say, greener pastures. It is the duty of our generation to determine if the influence of literature can be transposed onto the digital age, or, like Manzoni’s portrayal of social confusion and inequality, if literature in its written form will continue on in the way that it has been. Let the pioneering commence!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed